Ben Dell, managing partner at Kimmeridge, speaks with Hart Energy Editorial Director Jordan Blum Oct. 3 at Hart’s Energy Capital Conference in Dallas, Texas. (Source: Hart Energy)

With half as many public E&Ps in the market today as there were in 2017, Kimmeridge says there needs to be even fewer.

Bankruptcies and go-private transactions have taken down a few players, but consolidation is the real driver behind the decline.

The U.S. shale patch has been awash in a historic run of corporate consolidation, with some of the biggest public E&Ps getting plucked off the board in the past year.

Exxon Mobil closed a $60 billion acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources. Chesapeake Energy closed a $7.4 billion merger with Southwestern Energy. Chevron is acquiring Hess Corp. for $55 billion, though the deal has hit several snags.

But despite a record $192 billion in upstream M&A in 2023 and $51 billion in deals announced in first-quarter 2024, there’s still room for U.S. upstream to consolidate, according to the alternative asset manager Kimmeridge.

Even if every public E&P in the sector today merged with another operator—and then merged everyone together again—the industry would still be less concentrated than the financial, automotive and technology industries, Kimmeridge Managing Partner Ben Dell said.

“The E&P industry in the U.S. is still a highly disaggregated industry,” Dell said Oct. 3 during Hart Energy’s Energy Capital Conference. “I think there’s a lot of running room to go from a corporate M&A standpoint.”

By way of example, compare the E&P sector to the smartphone space, Kimmeridge suggested in a whitepaper published Oct. 7.

Nearly everybody owns a cellphone made by three or four companies. Apple “holds a commanding 55% share of smartphones,” while the top five companies collectively own 90% of the market, the firm reported. The smartphone sector is one of the most concentrated on Earth.

The E&P space remains much more highly fragmented: The top five E&Ps account for only 29% of domestic oil and gas production. To reach 50% of U.S. production requires stacking production from the top 14 companies together, according to Kimmeridge’s analysis.

The breakneck speed of E&P consolidation has drawn scrutiny from antitrust regulators. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission requested additional information about several proposed mergers and actually intervened in the Exxon-Pioneer and Chevron-Hess transactions.

“I think [FTC intervention] has been largely unwarranted,” Dell said, “because there’s no real argument about market domination in this space.”

RELATED

Kimmeridge’s Dell: Every US Basin Contains Both High-quality Inventory, Risk

‘They are worried’

Executives and analysts cite several reasons for the whirlwind of consolidation sweeping the U.S. shale patch.

Producers want scale and lower G&A costs. They crave quality drilling inventory able to sustainable profitability through periods of low oil and gas prices. They want to set themselves up for decades to come.

Kimmeridge thinks E&Ps “are combining because they are worried”—about their ability to squeeze more out of aging shale rock as drilling and exploration costs rise.

The firm analyzed recycle ratios across the industry, measuring cash flow per barrel produced versus the finding and development (F&D) costs to add a barrel to reserves.

While cash flow per boe has fluctuated due to volatile commodity price swings, “a consistent trend since the onset of COVID-19 has been rising F&D costs,” Kimmeridge said.

F&D costs have grown during the past three years, from a record low of $5/boe in 2021 to $10/boe in 2022 and $17/boe in 2023. Capital spending also grew each of those years.

And while spending rose 42% in 2022, proved developed reserves fell 31%. Spending rose another 28% the next year, yet reserve additions fell by 25%.

Of the 43 public E&Ps in the peer group, 40 experienced worse F&D metrics in 2023 than in 2022, Kimmeridge said.

The firm says the data starts to poke holes in the rosy picture the E&P sector has been painting since emerging from the pandemic: that there are years—maybe even decades—of high-quality shale drilling inventory yet untapped, and that declining capital efficiency should be worried about in the future.

Kimmeridge suggests that the decline is already underway, even as E&Ps publicly convey a different message.

“Why? Because nobody wants to admit that their time might be running out,” Kimmeridge said in the report.

E&Ps are delivering greater efficiencies by merging. Larger companies outperform on both cash flow per unit and F&D per unit metrics, thereby achieving higher recycle ratios compared to their smaller peers.

RELATED

Trauber: Inventory Drives M&A, But E&Ps Also Vying for Relevancy

Activist scorecard

As self-described fans of consolidation, Kimmeridge pats itself on the back for using successful activist investor campaigns to drive M&A and investor value in the E&P sector.

Internally, the firm is probably most proud of the three-way combination in Colorado’s Denver-Julesburg (D-J) Basin that yielded Civitas Resources in 2021.

Dell said that might have kicked off further consolidation in the D-J Basin. Not long after Civitas was formed, Chevron rolled up D-J Basin E&P PDC Energy in a $6.3 billion acquisition.

“Now, [the D-J] is one of the most concentrated basins in the U.S.,” Dell said. “I think it still has some of the best rock and best economics.”

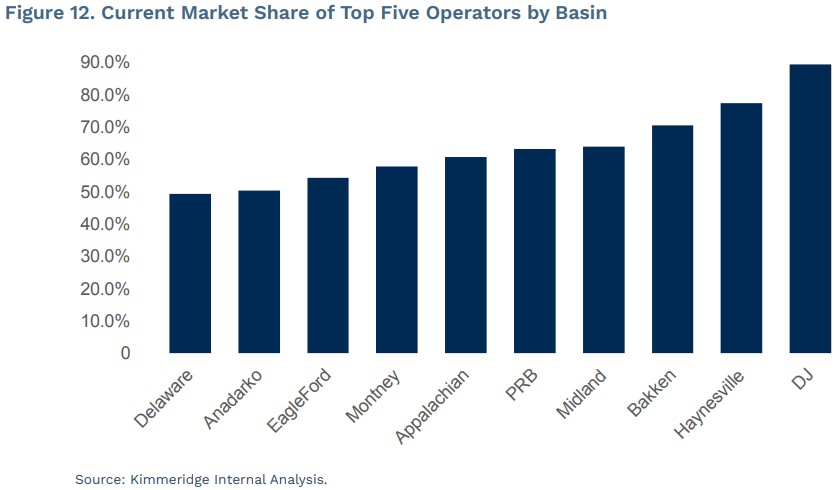

Indeed, the D-J Basin, by Kimmeridge’s analysis, is by far the most concentrated shale basin in North America. The top five operators in the D-J Basin own around 90% of the basin’s market.

It’s a significantly different story in other shale plays like the Delaware and Anadarko basins, where the top five operators make up just around 50% of total market share in their respective basins.

The lack of consolidation in the Delaware Basin “is perhaps the most surprising case” to Kimmeridge, because it’s one of the top basins in terms of returns and size.

Lateral lengths are increasing in the Delaware—but at a slower rate compared to the Midland Basin and other peers due to operators’ fragmented land positions.

The data suggests that “the Delaware is well-positioned for further consolidation,” Kimmeridge’s report said.

Kimmeridge expects to see additional consolidation, particularly in basins that remain highly fragmented.

There’s a “good question” about what happens to large-cap players like EOG Resources and Devon Energy: “Do they scale up? Do they combine? Do they sell?” Dell asked.

Smaller names like Permian Resources and Civitas also screen as attractive on a shrinking list of M&A targets.

RELATED

Decoding the Delaware: How E&Ps Are Unlocking the Future

SilverBow saga

Kimmeridge considers the Civitas story a win. Dell is more frustrated with how the firm’s takeover bid for SilverBow Resources turned out.

Kimmeridge, a major SilverBow investor, aimed to combine the public Eagle Ford E&P with its Kimmeridge Texas Gas assets nearby. The campaign may ultimately have forced SilverBow into making a deal—but not the deal Kimmeridge put forward.

Instead, SilverBow signed a deal to combine with Crescent Energy, an emerging upstream power that had quietly been lurking behind the scenes for years courting SilverBow.

SilverBow signing a deal with Crescent ended a long and public back-and-forth between Kimmeridge and the Eagle Ford E&P.

“At the end of the day, they took another path. They sold the company,” Dell said. “Shareholders made money. We made money. It kind of is what it is.”

But the SilverBow campaign certainly left a sour taste in Kimmeridge’s mouth.

“I’ll go down on the record saying this: I’ve never been involved in discussions with a more dishonest management or board,” Dell said.

RELATED

Growth Through M&A: The Making of an Eagle Ford and Uinta Giant

Recommended Reading

Utica’s Infinity Natural Resources Seeks $1.2B Valuation with IPO

2025-01-21 - Appalachian Basin oil and gas producer Infinity Natural Resources plans to sell 13.25 million shares at a public purchase price between $18 and $21 per share—the latest in a flurry of energy-focused IPOs.

What's Affecting Oil Prices This Week? (Feb. 3, 2025)

2025-02-03 - The Trump administration announced a 10% tariff on Canadian crude exports, but Stratas Advisors does not think the tariffs will have any material impact on Canadian oil production or exports to the U.S.

Utica Oil Player Ascent Resources ‘Considering’ an IPO

2025-03-07 - The 12-year-old privately held E&P Ascent Resources produced 2.2 Bcfe/d in the fourth quarter, including 14% liquids from the liquids-rich eastern Ohio Utica.

Utica Oil’s Infinity IPO Values its Play at $48,000 per Boe/d

2025-01-30 - Private-equity-backed Infinity Natural Resources’ IPO pricing on Jan. 30 gives a first look into market valuation for Ohio’s new tight-oil Utica play. Public trading is to begin the morning of Jan. 31.

The New Minerals Frontier Expands Beyond Oil, Gas

2025-04-09 - How to navigate the minerals sector in the era of competition, alternative investments and the AI-powered boom.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.